Learning to Create with Fungi

Designer Isabel Correa's experiments ask what interspecies collaboration looks like

Turning a corner in the basement of Columbia University's Teachers College, the heat suddenly rose by several degrees. "This is where it gets very hot," said designer and PhD candidate Isabel Correa, leading the way down the winding corridors. "It's good for the mushrooms." Down a smaller row of offices was the entrance to the 'Snow Day Learning Lab' — an ironic name, given the temperature — a makerspace where Correa experiments with mycelium. Inside, molded shapes and plastic bags were filled with fungi in different stages of growth, fuzzy white blocks of different shapes and sizes were strewn about, mushrooms sprouted from small containers of substrate.

Dried mushrooms on display at the Human–Nature Entanglements exhibition

The purpose of all the mushroomy objects was less about creating anything practical or tasty, and more about exploring a creative process that goes beyond the human mind. Engaging students with a living material — with its own needs, priorities and, perhaps, even its own perspective — creates an opportunity to collaborate with another form of life. Several floors above us in the Gottesman Libraries, these ideas and experiments took the form of an exhibition, called Human–Nature Entanglements — Explorations in Creativity Beyond Human.

Included among the exhibitions are beautiful objects made with mycelium

On a long table, a variety of colorful, textured objects sit under glass cases and jars. Some look like laser-cut rice cakes, others fused with colorful bioplastics, looking like laminated squares of sushi. The molds and design work were made by Correa and her students; the mycelium was sourced with a GIY Kit from Ecovative. They all represented a question posed to the fungi. Will it hold together in this shape? If not, why? Will it play nicely with home-brew bioplastics? Why does it grow one way in this environment, and another way in a different environment? On the table, video panels explained the process of working with this 'living clay', and along the walls colorful banners graphically illustrated the blurry lines between human and fungi.

Isabel Correa demonstrates a video display at the Human–Nature Entanglements exhibition

"To be honest, I'm not necessarily trying to do anything useful, it’s more about exploring what we can do together with this organism," said Correa. "I'm more interested in the relationship between the creator and the living organism, rather than whether they can create something useful or solve a problem. Maybe it’s more about solving our own internal problems as human beings"

"How can we cultivate this relationship?"

The project began in late 2019, when Correa visited community science lab in Brooklyn. She was struck by how scientists working in the arts considered the perspective of fungi, not just as subjects of study, but also as beings with their own agency. It was an open-mindedness and reverence for life that challenged science as she knew it. "I was expecting white males in white lab coats," she said. Shortly afterwards, the pandemic hit, and Correa began taking walks along Riverside park near Columbia as a way of staying active and engaged with nature.

"There's a nice path in Riverside Park called Forever Wild. I walked the path every day, and suddenly it was like mushrooms started to pop up everywhere. It's like you 'get the eyes', and see something that was always there. It's not like they just started to appear when I walked around there, but suddenly they were everywhere, all different and beautiful, and of course my daughter thought I was going crazy because I couldn't stop talking about them."

With people staying indoors, the constant sound of sirens and the feeling of the world falling apart all around, focusing on mushrooms became an unexpected source of peace, intrigue, and even hope. Fungi have an amazing ability to draw attention and inspire questions, and after first noticing them, they often start to appear unexpectedly in other areas of thought and daily life.

For Correa, who studies education design, fungi emerged as an educational space, where she could harness that wonderment as a part of the learning process, provoke questions, and in the process open up a deeper reciprocity with nature. In creating something that also created itself, as mycelium does, it's easy to wonder who is more the creator — the fungi, or the person who puts it into a mold? In the end, perhaps there isn't a definite answer because of how deeply entangled we all are, which is an interesting answer in and of itself.

The maker space where Correa's mycelium experiments originate

"We know so much about human creativity, but what about the creativity of nature? After all, aren’t we nature too? How does creativity emerge in our relationship with non-human beings?" Said Correa. "They are very active participants in the creative process. I see creativity as something that exists not enclosed in the human mind but in between actors and entities of various kinds: humans or not. Creativity is something that emerges from these interactions. And living materials can be so powerful because they are active, and have a clear agency of their own. If we could better understand our more-than-human partners and tap into their ways of creating the world, perhaps we can learn to more adequately join the flows of a world that is already going on.”

Among the objects on display are mycelium mixed with bioplastic

Interviews with biodesign experts led to working with the fungi to develop her own process, eventually adding sensors to get a better sense of the mycelia's responses, and testing different methods and materials to inspire dynamics of reciprocity and care. The exhibit displays some of the results of this experimentation, but the real work is centered on the study of creative interactions between learners and the living clay of mycelium.

In its final phase, Correa will work with middle schoolers for six weeks, testing some of the methods she has developed for encouraging mindful interplay with a non-human partner. At the end of the program, the students' co-creations will be displayed in Riverside Park, on the fungi's home turf, where the objects may stay like a gallery exhibition, or eventually return to the soil as they biodegrade. These are objects meant to spark ideas that can last much longer in the minds of students or the occasional curious walker.

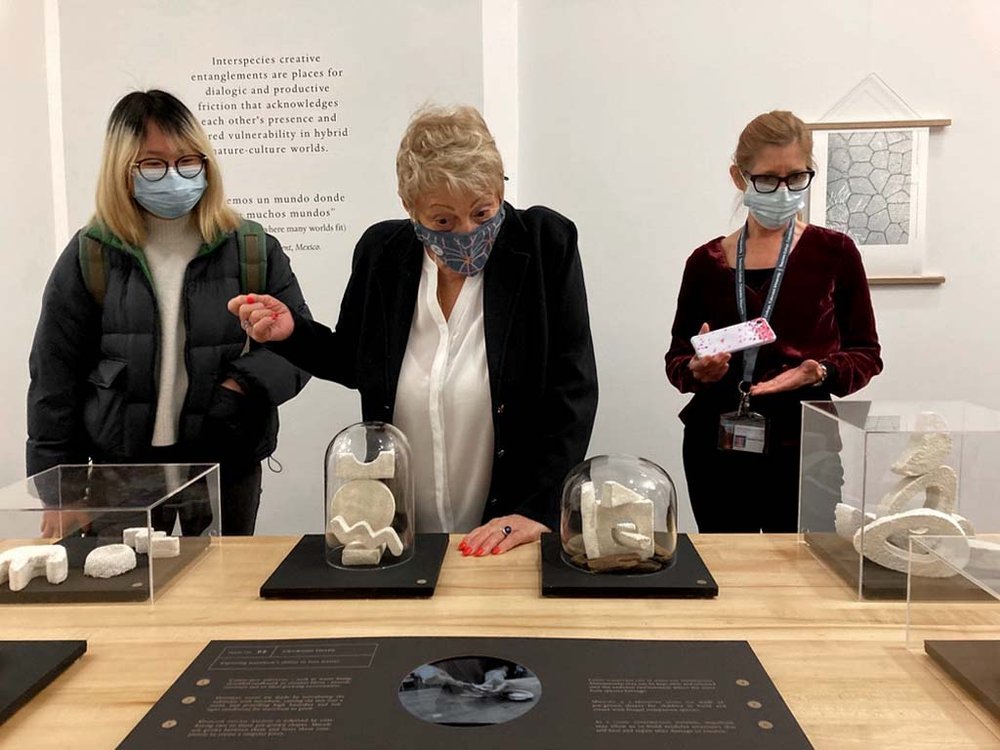

Guests observe the mycelium composite pieces on display in Human–Nature Entanglements

“Biodesign is to work in this very intimate encounter," Correa says. "You provide the conditions for the organism to grow in a certain way, but the organism will do its own thing. Sometimes you believe you are manipulating it, but the organism is manipulating you in its way too. It's kind of an awkward dance.”

Human–Nature Entanglements — Explorations in Creativity Beyond Human will be up until the end of April in the Gottesman Libraries at Columbia University.